Mary Thomas on the Supported Needle Method

Mary Thomas wrote about the history of knitting in her book, “Mary Thomas’s Knitting Book”, 1938, where she discussed a knitting method that employed various devices to support the right needle in a fixed position in order to free the hand to tension and move the yarn and speed up the work.

What is interesting about this is how old the method apparently is, how extensive its use was at one time in Europe, as well as in the United States as late as World War I. (As you will see, she also mentions an even older method using hooked knitting needles, but that discussion is for another day.)

The following is quoted from her book, and I included some of her inimitable illustrations:

SHEATHS, STICKS AND POUCHES

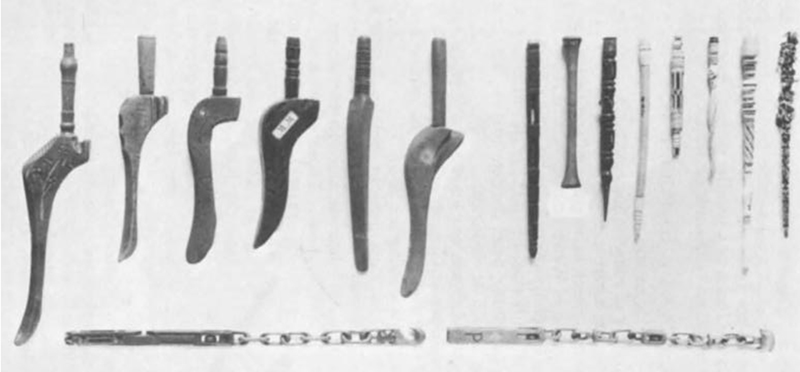

Knitting sheaths, or sticks, as they were sometimes called, are now a feature of museum interest, but at one time, when hand knitting was a vast and flourishing industry and speed a matter of pence, every knitter owned and used these implements. The group of Welsh knitting sheaths shown in Fig 12 are typical of the designs in universal use, those with the chains and hooks at the bottom being the most interesting. One of these, from Caerphilly, bears the date 1733-4. This hook had a special use, as will be explained.

Welsh Knitting Sheaths, Mary Thomas’s Knitting Book, Fig 12., by kind permission the National Museum of Wales

The lengthened sheath was known as a knitting stick, and Fig 13 shows three of German origin. Each sheath or stick had a small bore down the middle of the narrow end, large enough to admit a knitting needle.

Sheaths or sticks were used by both men and women knitters, and were worn on the right hip, tucked into a leather belt or through the strings of the apron. Those of scimitar shape in Fig 12 take the form of the body when slipped through the apron strings. The right needle was placed into the bore, and the right hand, thus freed of supporting the needle, was placed close up over the needle point, the forefinger acting as a shuttle, making the least possible movement and attaining a speed of 200 odd stitches a minute (See Fig 5)

(This claim has not held up to examination; in 2008, Hazel Tindall of Shetland won the title of The World’s Fastest Knitter, when she was timed at 262 stitches in 3 minutes. This is 85.3 stitches/minute, which is a more believable speed and one that seems attainable by mere mortals. When asked about this, however, Hazel laughed and told me she is not the fastest knitter in Shetland. JHH)

Balance was maintained with the thumb and other fingers, and these “played” the stitches downwards as they were knitted off the left needle with a rhythmical movement, similar to playing a flute, while the left hand in turn played the stitches up to the point of the left needle.

There seems no record of the knitting stick being worn on the left hip, by which we might suppose the introduction of the knitting stick (perhaps a Guild invention) inspired the transference of the working yarn to the right hand, and made obsolete the older left-handed hook technique.

The Shetland knitter to this day uses a knitting pouch as shown in Fig 14. This is a sort of oval pad stuffed with horsehair, covered with leather, and perforated with little holes, large enough to take the point of the needle. Into any of these holes the end of the needle is inserted (Fig 15), and the same incredible speed of 200 odd stitches a minute is attained, the hand working in the same way as with the knitting stick.

As the knitting grows in length it is attached to the left hip with a safety-pin, and until it is long enough for this purpose a length of wool is threaded through the base and wound round a safety-pin. The old workers had a hook, suspended from the belt or the end of the knitting sheath, for the same purpose (see Fig 12). By attaching the work to the back of the body in this way the necessary “pull,” which is such an air to speed, is obtained (See Fig 5).

This habit reflects some light on the old story that certain so-called “odd-minded” old women walked about with their knitting dangling from their backs! They did, and because this was a handy way of carrying the knitting. A Shetland knitter will drop her work at any moment and attend to other business, and, the job completed, resume her knitting with no loss of time. So well does she gauge her tension that the needles never fall out. On larger fabrics, cork guards will prevent this disaster.

But though the use of the knitting sheath may be obsolete to the modern knitter, the idea still survives in the rural districts of Britain and Europe. In northern Scotland the countrywomen will fix their right needle into a bunch of feathers thrust through the belt, while the Devonshire and Cornish women will use a twist of straw tucked through their apron strings, or make a long, narrow straw cushion which they call a knitting Cushion or Truss. These cushions measure about 10 in. x 3 in., and the straw envelopes of champagne bottles are now eagerly sought as stuffing, since they keep the cushion stiff and shapely. The envelope is cut across the middle and is sufficient for two cushions. The knitting pouch is still used in the Scandinavian countries and is exported from there, to the Shetlands. Old knitting sheaths and sticks were often handsomely carved, and decorated with mottoes or the initials of the owners. Luxurious ones were made of carved ivory or amber. Both Belgium and France (Boulogne) have very fine collections. Tin knitting sticks were made as an experiment in American during the Great War.